Basic Chinese Grammar and Sentence Structures // The Complete Guide

Basic Chinese Grammar is not hard – honestly!

Chinese grammar is relatively easy to get your head around once you’ve nailed the basics.

We’ll prove this to you right now with a rundown of all the key Chinese grammar points you need to know.

✅ Plus we’ve included example sentences and audio to help you consolidate your knowledge and perfect that pronunciation.

Let’s dive in!

Basic Chinese Grammar – Subject + Verb Sentence

Basic Chinese Grammar – Subject + Verb + Object Sentence

Basic Chinese Grammar – The 是 (shì) Sentence

Basic Chinese Grammar – The 有 (yǒu) Sentence

Basic Chinese Grammar – The 吗 (ma) Question?

Basic Chinese Grammar – Expressing “and” with 和 (hé)

Basic Chinese Grammar – Expressing Existence with 在 (zài)

Basic Chinese Grammar – Basic Negative Form of Verbs

Basic Chinese Grammar – Questions with Question Words?

Basic Chinese Grammar – The 把 (bǎ) Sentence

Basic Chinese Grammar – Expressing Experience with 过 (guò)

BONUS – Free Quickfire Grammar Quiz

Basic Chinese Grammar – FAQs

PSST – If you want an even more in-depth look into Grammar check out our Chinese Grammar Bank here. We are adding new articles all the time so you have a one stop place to understand every bit of grammar in Mandarin.

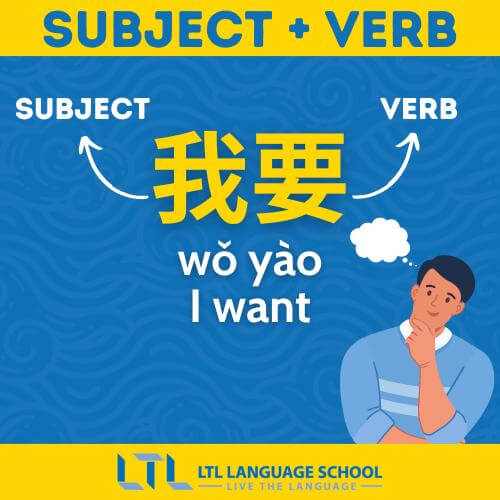

1. Subject + Verb Sentence

So for our first basic Chinese grammar point, we’re going to show you the simplest sentence structure in the Chinese language.

You can form very simple sentences with just two words, a subject + verb. For example:

👉 我忙 (wǒ máng): I’m busy.

我 (wǒ) means “I” (or in some cases “me”). 忙 (máng) means “busy”. Simple! Some other examples include:

| 我累 | wǒ lèi | I’m tired |

| 我要 | wǒ yào | I want |

| 你吃 | nǐ chī | You eat |

2. Subject + Verb + Object Sentence

The next basic sentence structure of Mandarin Chinese is the same as in English: subject + verb + object.

| 我爱你 | wǒ ài nǐ | I love you |

| 我吃苹果 | wǒ chī píngguǒ | I eat apples |

| 我们喜欢汉语 | wǒmen xǐhuān hànyǔ | We like Chinese |

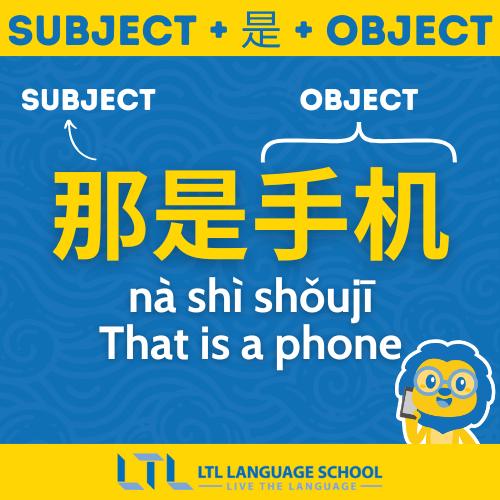

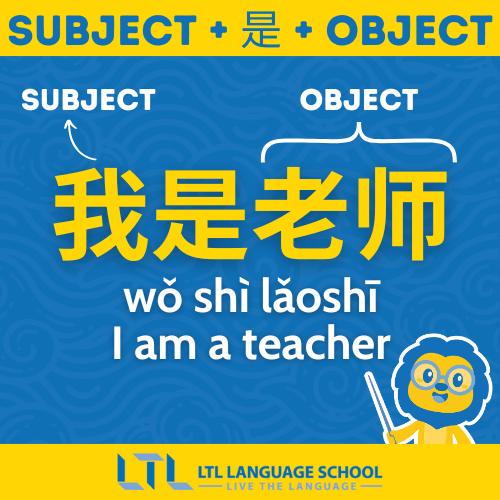

3. The 是 (shì) Sentence

This is a sentence in which the main verb is (well, obviously) the verb “shi” (是), which is best translated as the verb “to be” or “is”.

The sentence structure goes like this: subject + 是 (shì) + object.

At beginner level, 是 (shì) is usually used to identify people or objects. The position of the subject and object cannot be reversed, so for example the following sentence is incorrect:

❌ 学生是你。(The literal translation would be: “Student you are”.)

The correct form of this sentence would be:

✔️ 你是学生 (nǐ shì xuéshēng): You are a student.

Here are some other examples:

| 我是老师 | wǒ shì lǎoshī | I am a teacher |

| 她是演员 | tā shì yǎnyuán | She is an actor |

| 这是电脑 | zhè shì diànnǎo | This is a computer |

| 那是手机 | nà shì shǒujī | That is a phone |

4. The 有 (yǒu) Sentence

Another sentence structure common in Chinese is one where the main verb is 有 (yǒu). It means “to have” or “to possess”. For instance:

| 他有铅笔 | tā yǒu qiānbǐ | He has pencils |

| 我有中饭 | wǒ yǒu zhōngfàn | I have lunch |

| 我有生病 | wǒ yǒu shēngbìng | I’m sick [lit. I have sickness] |

Notice how the last sentence (“I am sick”) is different from the rest. With 有, you can use nouns and adjectives as well.

The 有 sentence can also be used to express existence. In this case, it is similar to the expression “there is/there are” in the English language, when meaning that something “exists” at a certain place.

This can sometimes be confusing to learners of the Chinese language (but also to Chinese people learning English, who tend to literally translate such sentences into English). Let’s take the next sentence as an example:

👉 我家有五口人 (wǒ jiā yǒu wǔ kǒu rén): There are five people in my family (literally: my family has five people).

In this example, the sentence would be translated with the “there is/there are” expression and not as “my family has five people”, since the verb 有 has a different meaning here.

Note: 有 is the equivalent of the English verb “to have”. The 有 verb does not, however, change in any way to indicate subject or tense.

75 Useful Academic Vocabulary 🎓 Let’s Go back to School in Chinese

Thinking of coming to learn Chinese? Good! As a present, we are getting you ahead of the rest with our hugely useful set of Chinese school vocabulary.

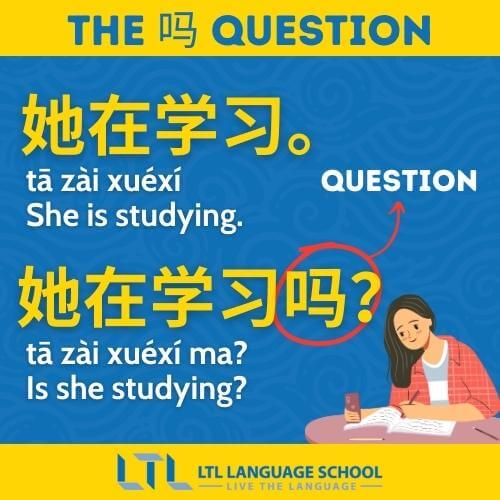

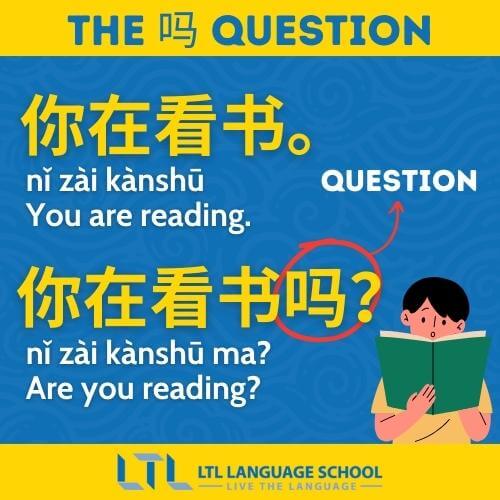

5. The 吗 (ma) Question

Asking a 吗 (ma) question is similar to asking a yes or no question in English.

To make a 吗 question, we simply add the particle 吗 at the end of the statement. This means that any statement can be turned into a question. Let’s look at a simple sentence, such as: “You like coffee.” (Who doesn’t?!)

❗ 你喜欢咖啡 (nǐ xǐhuān kāfēi): You like coffee.

We simply turn it into a question by adding the particle 吗 (ma) at the end of the sentence.

❓ 你喜欢咖啡吗? Nǐ xǐhuān kāfēi ma? Do you like coffee?

Some more examples:

| Statement | The 吗 Question |

|---|---|

|

你在看书

nǐ zài kànshū You are reading |

你在看书吗?

nǐ zài kànshū ma? Are you reading? |

|

她在学习

tā zài xuéxí She is studying |

她在学习吗?

tā zài xuéxí ma? Is she studying? |

|

他在喝水

tā zài hē shuǐ He is drinking water |

他在喝水吗?

tā zài hē shuǐ ma? Is he drinking water? |

For some more top tips on how to order a coffee, check out our blog.

But back to the grammar.

It is important to note that we cannot add the 吗 particle at the end of a sentence that is already a question. For example:

✔️ 你是谁? is already a question asking, “Who are you?”

❌ 你是谁吗?Nǐ shì shéi ma? Who are you “ma”? Doesn’t really make sense. It’s already a question without the “ma” particle.

To answer a 吗 (ma) question, one can give either an affirmative or negative answer.

In English, the word order and format of a “yes/no” question may change depending on a subject, tense and verb forms. But in Chinese, the form of the 吗 question never changes.

👉Pro tip – also, be careful with the use of the verbs 是 (shì) and 有 (yǒu), which we mentioned earlier.

Questions that contain the verb 是 (shì) should be answered with 是 (shì, affirmative) or 不是 (bú shì, negative). Those that contain 有 (yǒu) should be answered with 有 (yǒu, affirmative) or 没有 (méi yǒu, negative).

The question can also be affirmatively answered with 对 (duì).

The Complete Guide on How to Learn Chinese (in 2025) 🏆 13 Tips For Success

How to Learn Chinese? For a native English speaker, Chinese is an intimidating language! But it needn’t be as hard as you think if you follow these tips.

6. Expressing “and” with 和 (hé)

The character 和 (hé) is the most common way to express “and” in Chinese. But be careful! It is only used to link nouns. So don’t use it to link verse, adjectives or subordinate clauses.

The structure is the following: noun 1 + 和 (hé) + noun 2

| 你和我 | nǐ hé wǒ | You and I |

| 我有一只猫和一只狗 | Wǒ yǒuyī zhǐ māo hé yī zhǐ gǒu | I have a cat and a dog |

| 我的爷爷和奶奶都70岁了 | Wǒ de yéye hé nǎinai dōu qīshí suì le | My grandpa and grandma are both 70 years old |

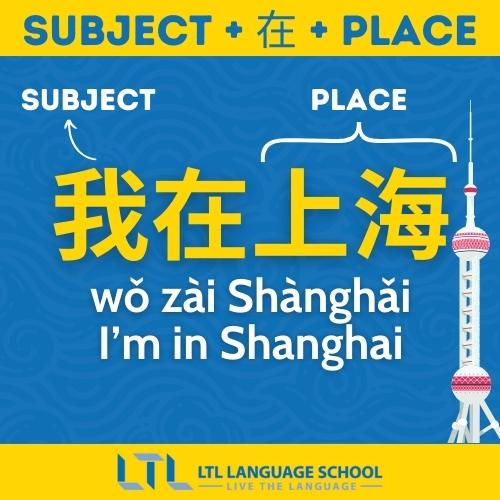

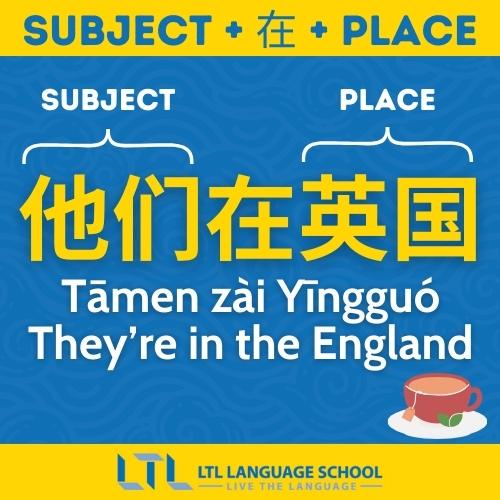

7. Expressing Existence with 在 (zài)

The verb 在 (zài) can be used to express “existence in a place”. This is similar to English in which we use “to be at” or “to be in” to express the same.

The structure is the following: subject + 在 (zài) + place

Let’s look at the following examples.

| 我在上海 | Wǒ zài Shànghǎi | I am in Shanghai |

| 他们在英国 | Tāmen zài Yīngguó | They are in England |

What do we see in these examples? Although it can be tempting to use a verb here, there’s no need for it. In fact, using a verb here would be grammatically incorrect. Here, 在 functions as a verb, so there is no need for 是 (shì) or 有 (yǒu) or any other verb.

在 can also be used as a preposition or adverb.

| 我在学中文 | Wǒ zài xué zhōngwén | I am learning Chinese |

| 你在游泳 | Nǐ zài yóuyǒng | You are swimming |

| 他在买菜 | Tā zài mǎi cài | He is buying groceries |

8. Basic Negative Form of Verbs

In Chinese, there are basically two adverbs used for negation: 不 bù and 没(有) méi(yǒu). Both are placed before the verb in a sentence.

👉 Note that 是 (shì) cannot be negated with 没/有 (méi/yǒu), and 有 (yǒu) cannot be negated with 不 (bù).

不 (bù)

不 (bù) is used to negate an action done at the present:

| 我今天不学中文。 | Wǒ jīntiān bù xué Zhōngwén. | I am not studying Chinese today. |

| 我今天不去了。 | Wǒ jīntiān bù qùle. | I won’t go today. |

It can also be used to negate an action in the future:

| 明年我不去中国。 | Míngnián wǒ bù qù Zhōngguó. | I won’t go to China next year. |

| 我明天不上学。 | Wǒ míngtiān bù shàngxué. | I will not go to school tomorrow. |

Or to negate a habitual action:

| 周末我不看书。 | Zhōumò wǒ bù kànshū. | I don’t read books on the weekend. |

| 我通常不唱歌。 | Wǒ tōngcháng bù chànggē. | I don’t usually sing. |

没有 (méiyǒu)

没 (méi) is used to negate 有 (yǒu) — 没有 (méiyǒu) — and means that one “does not have”. The negative form of 有 (yǒu) is always 没有 (méiyǒu), never 不有 (bùyǒu).

| 我没有中国朋友。 | Wǒ méiyǒu Zhòng uó péngyǒu. | I don’t have Chinese friends. |

| 我的卡里没有钱。 | Wǒ de kǎ lǐ méiyǒu qián. | My card does not have money. |

WANT MORE? We’ve prepared a more in depth post about negation in Mandarin here.

9 Surprising Reasons That Learning Mandarin Isn’t Nearly As Hard As You Think

How hard is it to learn Mandarin? In many ways, it’s a lot more straightforward than other Asian languages and even European languages! Here’s why…

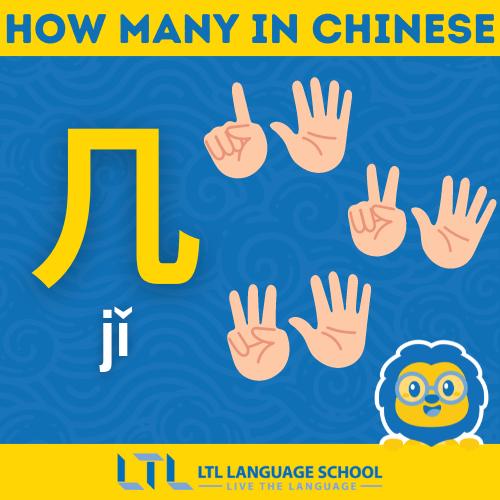

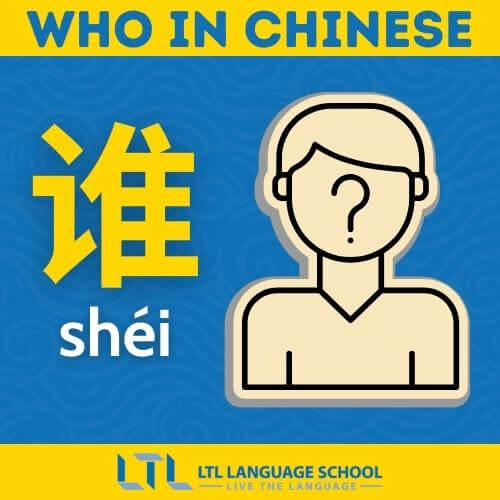

9. Questions with Question Words?

First things first, let’s look at some of the most common question words in Chinese. Look closely at this list, it will come in handy often!

| 谁 | shéi | who |

| 什么 | shén me | what |

| 哪里 | nǎ lǐ | where* |

| 哪个 | nǎ ge | which |

| 什么时候 | shén me shí hou | when |

| 为什么 | wèi shén me | why |

| 怎么 | zěn me | how |

| 多少 | duō shǎo | how many |

| 几 | jǐ | how many (any number under ten) |

*Note: 哪里 (nǎ lǐ) is different from 那里 (nà lǐ).

Alone, 哪里 (nǎ lǐ) is a question — 哪里? Where? 我的笔在那里?Where is my pencil?

那里 (nà lǐ) is a statement saying something is there. Where is my pencil? 那里。There. 你的笔在那里。Your pencil is there.

Now, let’s talk about the most common structure of questions which use question words.

The question word is placed in relation to (meaning, in the position of) the word you’re asking about. Here are some of the most common sentence structures:

Question word + verb + (object)

| 谁教你中文? | Shéi jiào nǐ zhōngwén? | Who teaches you Chinese? |

| 什么东西到了? | Shénme dōngxī dàole? | What thing arrived? |

Subject + verb + question word

| 你去全家买了什么? | Nǐ qù quánjiā mǎile shénme? | What did you buy at FamilyMart? |

| 我的铅笔在哪里? | Wǒ de qiānbǐ zài nǎlǐ? | Where is my pencil? |

Question word + subject + verb + (object)

| 多少人要参加明天的会? | Duōshǎo rén yào cānjiā míngtiān de huì? | How many people will attend tomorrow’s meeting? |

| 为什么天是蓝色的? | Wèishéme tiān shì lánsè de? | Why is the sky blue? |

Subject + verb + question word + (object)

| 你昨晚吃了什么? | Nǐ zuówǎn chīle shénme? | What did you eat last night? |

| 这双鞋是谁的? | Zhè shuāng xié shì shéi de? | Whose shoes are those? |

As you can see, the sentence structure of a question is the same as a statement. The main difference is that a question has the addition of question words to make it a question. This is different from English, where questions and statements have very different sentence structures.

Keep the last section in mind! The particle 吗 (ma) cannot be used in questions with question words, because 吗 (ma) is a question word itself.

WANT MORE – We’ve prepared a more in depth post about all the key questions in Chinese here.

10. The 把 (bǎ) Sentence

The 把 (bǎ) sentence is a useful structure for making longer sentences. The focus of the 把 (bǎ) sentence is on the action and its object.

This is a really common sentence pattern in Chinese, but can (at least at first) feel a bit weird for English speakers.

A basic sentence in Chinese is formed with a subject-verb-object (SVO) word order, as in English:

Subject + [verb phrase] + object

In a 把 (bǎ) sentence, things are changed and the structure goes like this:

Subject + 把 (bǎ) + object + [verb phrase]

We can see now that the object has moved, it is preceded by the 把 (bǎ) and the word order is now in fact an SOV word order.

So, why use this sentence which is somewhat weird (well, at least weird for English speakers)?

Though you may think you’ll never need the 把 (bǎ) sentence, they’re quite convenient. Let’s look at the following example:

把书放在桌子上 。

Bǎ shū fàngzài zhuōzi shàng. Put the book on the table.

How would you say this without the 把 (bǎ) construction? You might try this: 书放在桌子上 (Shū fàng zài zhuōzi shàng.)

While this sentence is grammatically correct, the meaning may change. 书放在桌子上 (without 把, bǎ) can mean the same thing, but it could also mean “The book is on the table”. It is the answer to two questions: (1) where should I put the book?, and (2) where is the book?

The 把 (bǎ) sentence is clearer. 把书放在桌子上 is a command; you are telling someone to put the book on the table. There is less room for confusion.

Here’s another example of a 把 (bǎ) sentence.

她把我的手机放在她的包里了。

Tā bǎ wǒde shǒujī fàngzài tāde bāo lǐ le. She put my phone in her bag.

In the 把 (bǎ) sentence, we put emphasis on the object and what happens to it. This is something that is useful to remember if you don’t know when to use this sentence structure.

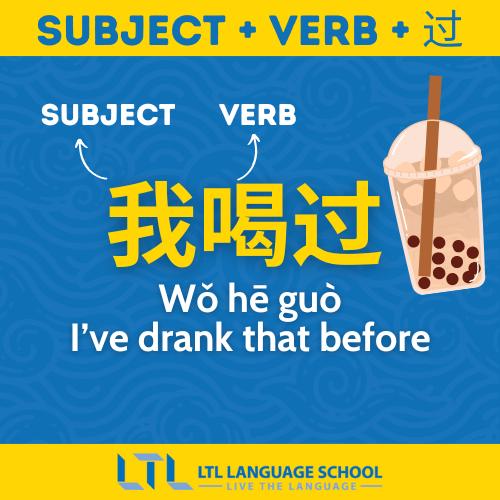

11. Expressing Experience with 过 (guò)

The particle 过 (guò) is used to express that an action has been experienced in the past. The basic structure is formed so that you just place it after the verb:

Subject + verb + 过. The particle “guo” can also take on an object.

| 我试过。 | Wǒ shì guò. | I’ve tried that before. |

| 我喝过。 | Wǒ hē guò. | I’ve drank that before. |

| 我弄过。 | Wǒ nòng guò. | I’ve done that before. |

The usual sentence structure with an object is the following: Subject + verb +过 (guò) + object.

This 过 (guò) expression is used to talk about if something has ever happened. In that respect it is similar to the present perfect tense in English and how it is used to express past experiences.

It is useful to think about how in English, you would say “I have been to London” or “I have travelled to Shanghai” to express past experience.

过 (guò) is used in the same manner in Chinese.

| 我也吃过日本菜。 | Wǒ yě chī guò Rìběn cài. | I’ve also eaten Japanese food. |

| 你看过这部电影吗? | Nǐ kàn guò zhè bù diànyǐng ma? | Have you watched this movie? |

| 我去过加拿大。 | Wǒ qù guò Jiā’nádà. | I’ve been to Canada. |

We form the negative sentence using 没 (méi) and the structure is the following: Subject + 没 (méi) + verb + 过 (guò) + object.

You can also use 没有 (méiyǒu) for emphasis.

| 他没坐过飞机。 | Tā méi zuò guò fēijī. | He has never flown in a plane. |

| 我没学过西班牙语。 | Wǒ méi xué guò Xībānyáyǔ. | I’ve never learned Spanish. |

| 你没来过我的家。 | Nǐ méi lái guò wǒ de jiā. | You’ve never been to my house before. |

Asking questions with 过 (guò)

A few of the example sentences above were questions, but you might like to see a couple more ways you can ask questions with 过 (guò).

The following sentences are the same question structured in different ways, all grammatically correct. They’re asking, “Have you been to Japan?”

| 你去过日本吗? | Nǐ qù guò Rìběn ma? |

| 你有没有去过日本? | Nǐ yǒu méi yǒu qù guò Rìběn? |

| 你去过日本没有? | Nǐ qù guò Rìběn méiyǒu? |

This is a similar question: 你没去过日本?Nǐ méi qù guò Rìběn? You’ve never been to Japan?

Using 过 (guò) with 从来没有 (cónglái méiyǒu)

Since 过 (guò) is used to talk about experience in the past, it can be combined with 从来没有 (cónglái méiyǒu) to express something that has never happened.

Structure: Subject +从来没有 (cónglái méiyǒu) + verb + object

| 你从来没有去过日本? | Nǐ cónglái méiyǒu qù guò Rìběn? | Have you never been to Japan? |

| 我从来没有吃过这么多! | Wǒ cónglái méiyǒu chī guò zhème duō! | I’ve never eaten this much before! |

| 你从来没有看过《冰雪奇缘》? | You’ve never watched Frozen? | Nǐ cónglái méiyǒu kàn guò “bīngxuě qí yuán”? |

We hope you found this post useful! Let us know if you want us to cover any other topic, grammatical or not!

WANT MORE? We spent hours putting together these Free HSK Quizzes which are excellent are giving you a rough idea on your Chinese level. Come check them out.

BONUS – Free Quickfire Grammar Quiz

OK, so now you’ve got the basics nailed down it’s time to see how much you remember.

To help you we’ve prepared a quick quiz which is only 15 questions long.

Get your results instantly upon submission and see how well you did. Any questions, drop us a comment below!

We hope it’s useful

Immersing yourself in real-life situations — like spending time in Xi’an learning Chinese and chatting with locals — can make grammar patterns feel much more natural.

Fancy delving into the world is other languages? Check out these posts we think you’ll like also:

- Discover the basic grammar points in Korean

- Learn how to use and apply Japanese verbs

- Tackle Reflexive Pronouns in Spanish

- Unearth a gem – our very own Chinese Grammar Bank

Happy studying!

Basic Chinese Grammar — FAQs

How do you say “grammar” in Chinese?

Grammar in Chinese is 语法 (yǔfǎ).

Is Chinese grammar easy?

Chinese grammar may be a bit confusing at first, but it’s actually far, far easier than that of other languages!

Once you understand the basic structures, Chinese grammar is pretty simple to use.

How do you ask a question in Chinese?

Quite simply by adding 吗 (ma) onto the end of a sentence allows the sentence to become a question.

For example I could say “I’m full up”.

吃饱了

Wǒ chī bǎo le.

Now simply add on “ma”.

吃饱了吗?

This has no become a question. Are you full? Simple!

How do you express negation or a negative in Chinese?

In Chinese, there are basically two adverbs used for negation…

不 (bù) and 没/有 (méi/yǒu).

Both are placed before the verb in a sentence but have different uses which you can find out more about here.

How do you say “Why” in Chinese?

Why in Chinese is 为什么.

How do you say “How” in Chinese?

How in Chinese is 怎么.

How can I learn Chinese grammar?

You should understand the basics of Chinese sentence structures first before moving on to more difficult ones.

Here, we’ve outlined basic sentence structures, questions in Chinese, negative forms of verbs, and expressing experiences.

Want more from LTL?

If you wish to hear more from LTL Mandarin School why not join our mailing list.

We give plenty of handy information on learning Chinese, useful apps to learn the language and everything going on at our LTL schools!

Sign up below and become part of our ever growing community!

Hi, my name is Ilaria. I am from Italy and I am a Student Advisor at LTL. Fancy coming to study with us in China? Drop me a message.

Hi, my name is Ilaria. I am from Italy and I am a Student Advisor at LTL. Fancy coming to study with us in China? Drop me a message. Hi, my name is Mojca. I am from Slovenia in Europe and I work as a student advisor at our Shanghai school.

Hi, my name is Mojca. I am from Slovenia in Europe and I work as a student advisor at our Shanghai school.

19 comments

[…] memiliki arti “kebas” (má 麻), “kuda” (mǎ 馬), “menegur” (mà罵), atau komponen grammar yang hadir di akhir pertanyaan ya atau tidak (ma […]

[…] we’ve used the 对 grammar structure again to state the relationship between two things (you and your partner once […]

Thanks for share this article. it's quite helpful to me.

Best regards, Griffin

Our pleasure Griffin!

Honestly Chinese grammar aint hard. Korean way harder!

Yes we've heard Korean can be very tricky for grammar!

hi please help me to learn chinese

Thanks, great post and useful pointers for beginners/intermediate students

🤩

[…] – Basic Grammar with […]

很难,但我试试

加油Gloria

Helpful article. Thank you LTL

Glad to hear it Gianna. We've already got a Grammar Bank which goes into even further detail. Hope it's useful 🤩 https://flexiclasses.com/chinese-grammar-bank/

Where can I learn the letters for Chinese (pinyin).

Right here >>> https://ltl-beihai.com/pinyin-chart/

This is a useful for self study students who are always want to improve their skills.

We're glad you found it helpful!

Haha, I've been mildly studying Chinese for the past month but I can't help but laugh at the option that lets viewers listen to how the sentences are said. The sentences are pronounced like Siri seeing Chinese for the first time without knowing any of the Chinese pronunciations.